An identity adrift: Canadian-born Estonian DOP Alar Kivilo talks about his cosmopolitan identity, working in Hollywood, pulling a fast one on Bruce Willis, and the enormous shot in the arm that the production of ‘Tenet’ brought to the Estonian film industry

Born in Canada, living and working in Los Angeles, an Estonian at heart – Alar Kivilo is as cosmopolitan as one can get. The DOP who shot the box office hit The Blind Side that brought Sandra Bullock the Academy Award talks about his drifting identity, how he once fooled Bruce Willis on the set of Hart’s War, what Estonia has to offer for filmmakers and how Estonians earned a reputation of being hard workers on Christopher Nolan’s Tenet.

Made in Tallinn, Estonia by Liisi Rohumäe.

Cover photo by Suzanne Hanover.

Even if people don’t know you, they have most definitely seen any of the films you have worked on. You have made big studio films, small indie dramas. How do you choose which projects to do?

That’s always a struggle, you have to balance so many things. On the one hand you have to make a living, but also you have to be kind to your creative soul and not do things solely for money. It has always been a balancing act for me. But it always starts with the script and if it really appeals to me or if I find elements in it that appeal to me. Sometimes that can lead you astray too, you find something that really appeals to you, but for different circumstances or the vision of the director they can go a different route and ignore what initially appealed to you. I know that’s happened to me once.

Because of that, the second most important thing is to meet with the director and see if there is chemistry between us because it’s really like a marriage. It’s chemistry… you are spending such a large chunk of your life on a film project… You don’t have to see everything exactly the same, but there has to be this dance between the two of you, a kind of creative dance…and the increased energy that comes from two people rather than doing it by yourself. I get sent scripts, and sometimes it’s an indie, sometimes it’s a bigger film, but in the end, the final decision is always because of my meeting with the director. Both on my side and their side.

Very often big films come with big names. The list of huge stars you’ve worked with is very long. Sandra Bullock, Cameron Diaz, Kevin Bacon, Diane Lane, Keanu Reeves, Bruce Willis. You have even been on set with Frank Sinatra. I am curious, is there such a thing as lighting a star?

Yeah, definitely there is. I did an HBO movie called Normal with Tom Wilkinson and Jessica Lange. Basically, we wanted her to look great, and Tom, we wanted to look natural. Very often they would be in the same shot together, so I would have light coming from a window lighting Tom Wilkinson naturally, but then on Jessica’s side of the same frame, there would be a sea of flags and scrims just to direct the light on her in the most favourable, cosmetic way. It does happen.

But eventually, the actors see themselves on the screen and they care about their looks. Actually, on Hart’s War, Bruce Willis who has had so much experience as an actor, had a notion which particular lens would be the best for him… and I tried that, but he was playing this tough camp commandant in a prison of war camp and I just felt he needed to have this strong presence and the lens that he was suggesting would have softened him. So I ended up using the lens that I thought was right, but I told the camera assistants to mark… because you always mark which lens is on the camera… I told them to put his numbers on that lens. So he was, “Oh, you’re using the 65, great.” But it was actually a 50.

And he wouldn’t know the difference when he saw it?

No, I don’t think he… No.

So you have to cater to egos sometimes?

Yeah… I have been very lucky and you’re right, the list of big names is long. And yet, I have been lucky that I never really had a bad experience with any of them ,except maybe one. But we won’t talk about that.

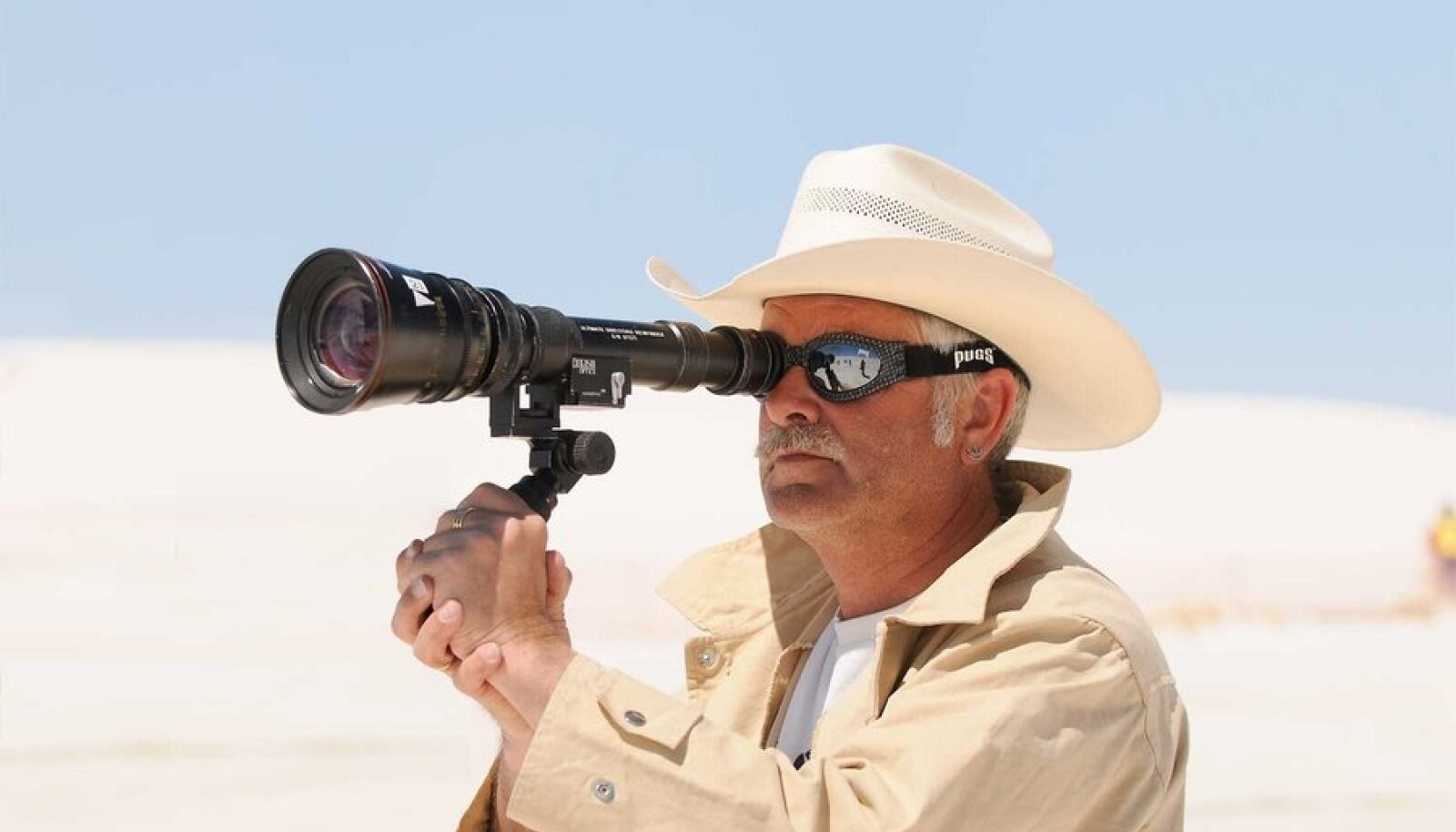

Alar Kivilo. Photo by Rick Thomas

You also work on your own projects and I know you are writing scripts and you have made one short that you shot in Canada, kind of a meditation on time and memories, called “Through Ice and Time”. It’s completely wordless and shot outside in a national park, so as you have said before that you see life as a frame quite often, are there places here in Estonia as you go around and think, God I wish I could shoot a movie here?

Absolutely. One of the joys of film-making, is coming to a place that you don’t really live in. Even though I have a strong connection to here and spend most of my summers here, I don’t really live here. The benefit of that is that I see things local people never notice. So yes, I see so many opportunities filmicly in Estonia. There are such a variety of looks here.

You can still discover the sort of fallen apart Tarkovsky Stalker type of Soviet structures. Beautiful, beautiful nature can be found. Medieval towns. Cobblestone streets. These are more of the postcard aspects of it, but there is so much to be seen here. I always get stimulated when I’m here. And nature… this is something very specific to Estonia… the bogs and the marshes are really something you don’t get to see anywhere else.

I spent a lot of time on the Canadian East coast directing and shooting commercials for Newfoundland and there I found a lot of connections to Estonia. The rugged seacoast and the rocks. I like rocks, maybe because of my name (editor: the name Kivilo includes the word “kivi”, meaning rock in Estonian). There is that connection. But yeah, there is so much that inspires me here.

Now that one big Hollywood film has come to Estonia and is opening worldwide, I, of course, mean Christopher Nolan’s Tenet. Have you had a chance to see it?

I haven’t seen Tenet yet, but I did get the opportunity to get feedback about what the experience was like. I did some additional photography on the movie Fast and Furious 9 in Los Angeles and there was a second assistant director that I’ve worked with before on another film and a couple of other crew members who all worked on Tenet and they were just gushing about Tallinn… Tallinn as a city, Tallinn as a place, the restaurants. But they were also gushing about the crew, they thought the crews were top-notch, the organization was top notch. They loved it. I felt really proud.

In fact, there was one production assistant, who after Tenet finished shooting in Tallinn and then in Italy and also somewhere else… it was a long shoot… she so enjoyed Tallinn that once the shoot wrapped she flew back to Tallinn just to be here. Just to continue experiencing it.

You mention nature and these different Soviet-era buildings, do you think there is a certain type of project that would benefit from filming here in the Baltic region or in Finland?

It’s hard to tell, it’s so script-specific. I think, just to put on a producer’s hat for a second, and especially a producer coming from America or English-speaking countries, the big benefit here is that everybody speaks English very well. So that’s not a problem. There might even be, because of it’s post-Soviet baggage, a tendency to lump Estonia together with other places that are perhaps a bit more haywire and not as buttoned-down as Estonia is. Estonia is really like going to Scandinavia…like Sweden or Finland. There is a very strong work ethic here and generally, they are very cultured people who have a very wide world view, which I think again is beneficial.

In filmmaking, you need to be flexible and you need to understand and intuit that people might be after something else. You have to be able to translate that. In terms of a very specific project, the big thing nowadays is to shoot in places that aren’t necessarily the places in the script, so part of the joy of coming here could be lost. But if you want come to Tallinn and still find places that look like Santa Monica or anything else, I think that’s possible here, too. There seems to be such a breadth of possibilities here in terms of locations.

What about your identity? You were born in Canada, your parents are Estonian, you live in the States, and yet you come back to Estonia quite often. We are actually meeting in Estonia right now, so how would you describe your identity and is there something here in the Baltic region that still kind of tethers you here?

I think the whole question of identity is something I… maybe struggle is the wrong word to use, but something that has been front of mind my whole life. As you said I was born in Montreal which further adds a dimension because Montreal is a bilingual city. There was a French-speaking side to the city, and an English-speaking one, where I grew up. But I didn’t speak English until I was six because the language we spoke at home was Estonian. So I had a strong beginning in terms of my Estonian roots and feeling connected to Estonia. Also, my father was an active community leader in the Estonian ex-pat society, who had a dream that one day maybe Estonia will be free again, and worked really hard to keep that dream alive. So I kind of grew up indoctrinated in that milieu. The language obviously was a big part of it and I have never lost the language.

I remember I came to Estonia for the first time in 1972 which for me was an amazing experience because up until that point it had been this sort of mythical magical place that my parents talked about. And my parents left when they were maybe 14 or 15 so their impression of the country was also mythical, I would say. So to me, it was such a revelation to come to a country that was an actual country… there are all sorts of people here with all sorts of professions… it’s an actual country and everybody spoke my language. It was quite amazing.

When I arrived in Estonia I thought it would be very emotional after a lifetime of hearing about it, but surprisingly, arriving wasn’t that emotional. When it came time to leave my relatives gave me a big bouquet of flowers, and as the ship was leaving I threw my bouquet of flowers into the water… and remember, everything to me is a shot… so I saw the bouquet of flowers floating in the sea and I slowly tilted up to see the receding silhouette of Tallinn. Then I almost broke down.

So yes identity, it’s an interesting question. When I finally moved to Los Angeles 23 years ago, for some reason, there I felt the most comfortable of all the places I have ever lived in and I attribute it to the fact that so few people are actually from California. It seems to be the place where people come to, gravitate to, like a melting pot. And I was just another one of those people, I felt really comfortable there.

But that said, I came to Estonia in 88 as well, to do a documentary about the first-ever rock concert in the Soviet Union called Rock Summer. I was working as a cameraman and also as a translator for the people doing interviews. I was there with all the Singing Revolution politicians and the musicians. I guess my biggest highlight from that time was translating for Johnny Rotten. I loved what he said in a press conference. The foreign press was asking him, how does it feel to be in Russia? This was back in 88 before Estonia had gained independence, and he said, I am not in Russia, I am in Estonia. That was very astute of him – he understood! – which was really cool! So obviously something like that had an effect on me. I guess it’s always been a big part of my identity. So, in 1988 I also met my present wife here, so we speak Estonian at home. We have two children, they speak Estonian. They also speak French. So, it’s sort of a United Nations family.

Once a film you’ve shot is out, how much do you follow the box office, how much do you care about it. I mean this goes to reviews as well. Obviously, you filmed The Blind Side which was a huge box office success and Sandra Bullock got an Oscar for her role. How much does that matter to you? Even talking about reviews, you don’t really find much in them about cinematography.

Yeah, that depends… It’s usually one sentence. One sentence that can either destroy you or make you jump for joy. But you’re right, it’s rarely mentioned. I think cinematography, in general, is a misunderstood mysterious craft that a lot of people don’t quite understand. Part of that proof is you see so many movies win Oscars for cinematography that were period costume dramas. They don’t realize how tricky it is to actually shoot inside under different changing conditions trying to make one-minute feel consistent even though you’re filming it for two weeks.

But yes reviews, obviously I read them, but to me, it’s all about the work. And the process. One of my most enjoyable parts of the work is the pre-production before the film starts to shoot. That is when we are just discussing things and looking at images and listening to music, and having long chats and talks and throwing ideas back and forth. That creative spirit is so much fun. And then the actual shooting of it is a lot of fun, too. And for me, the final process of colouring the film is where I get one more chance to subtly inform the story… to reinforce aspects of the story. So all that is exciting to me. Obviously, it’s really nice when it does well and it’s through the roof and it wins Oscars, but to me, the making of the film was what really counted.

fun. Actually, speaking of reviews, I did get a live TV review from Sandra Bullock during the SAG awards when she won and she called me out by name and talked about how she had looked in the morning and how she ended up looking on film. She attributed that to me. I can’t deny, that was a very special moment.

Is there something you would like to add before we wrap?

Just to reiterate a previous point, there are world-class filmmakers here in Estonia. And a lot of them are young filmmakers, which is exciting since usually with youth comes passion. In Estonia, there is a strong can-do spirit. A common-sense approach. People use simple logic for things… it’s not a place that is overwrought with out of control emotions… This is a place of serious filmmaking.